Contender or Coffee Getter? Here’s Your "Authentic" Writing Assessment

How professional military education incentivizes sloppy writing

“Authentic assessment” is the new buzzphrase in officer professional military education (PME). Joint policy states that authentic assessments “approximate conditions under which the graduate would be expected to achieve the same outcomes in the operational environment.” Translation: Students show what they’ve learned by performing real-world tasks.

Are PME writing assessments authentic? Hardly.

PME uses many written assessments but few, if any, writing assessments. The difference matters. A written assessment evaluates a student's mastery of a subject. For example, a written leader case analysis assesses whether students can apply learned leadership skills. However, the focus is on leadership, not writing; the assessment uses writing as a means to an end. It is not a writing assessment since its purpose is not to evaluate writing skills.

But can’t we measure both writing and a target subject at the same time? In other words, can’t we improve students’ writing skills by having them write papers on various subjects—such as history, leadership, planning, etc.? This “twofer” strategy is tempting because it allows schools to avoid dedicating valuable classroom time solely to writing. Students learn writing by osmosis; schools teach it on the cheap.

We tried the “twofer” strategy at the US Army CGSC. Several years ago, commanders told us that CGSC graduates wrote poorly. In response, we added written assessments across many topics, hoping to improve students’ writing skills without taking the time to teach them how.

The strategy failed. Writing more didn’t improve students’ writing skills. In fact, it likely made them worse. Why? Because a high volume of written assessments incentivizes poor writing.

The problem starts with grading rubrics. Instructors grade written assessments using rubrics weighted toward the target subject. In a leadership paper, for example, 80% of the grade might assess leadership analysis, leaving 20% for writing quality—organization, clarity, and correctness.

This weighting makes sense because instructors must evaluate target subject mastery. Weighted rubrics ensure students pass if they understand the target subject, even if they write poorly. Likewise, weighted rubrics ensure students fail if they lack subject mastery, even if they write well.

The drawback of this approach is that it masks students’ weak writing skills. Despite writing poorly, students can and often do earn passing grades on written assessments. Worse, they interpret these repeated successes as proof that they write well. They move from paper to paper, writing poorly but passing, increasingly convinced they write well enough for professional work.

Faculty and PME curricula contribute to the problem. Some instructors lack the skill or willingness to critique the writing and give tough, honest feedback. Or they prioritize subject matter over writing quality. Even when instructors offer detailed feedback, students have little incentive to improve because PME curricula often prioritize quantity over quality. Weighted rubrics do not reward extra time spent making writing clear and correct. Producing a large volume of mediocre work is the most efficient path to graduation.

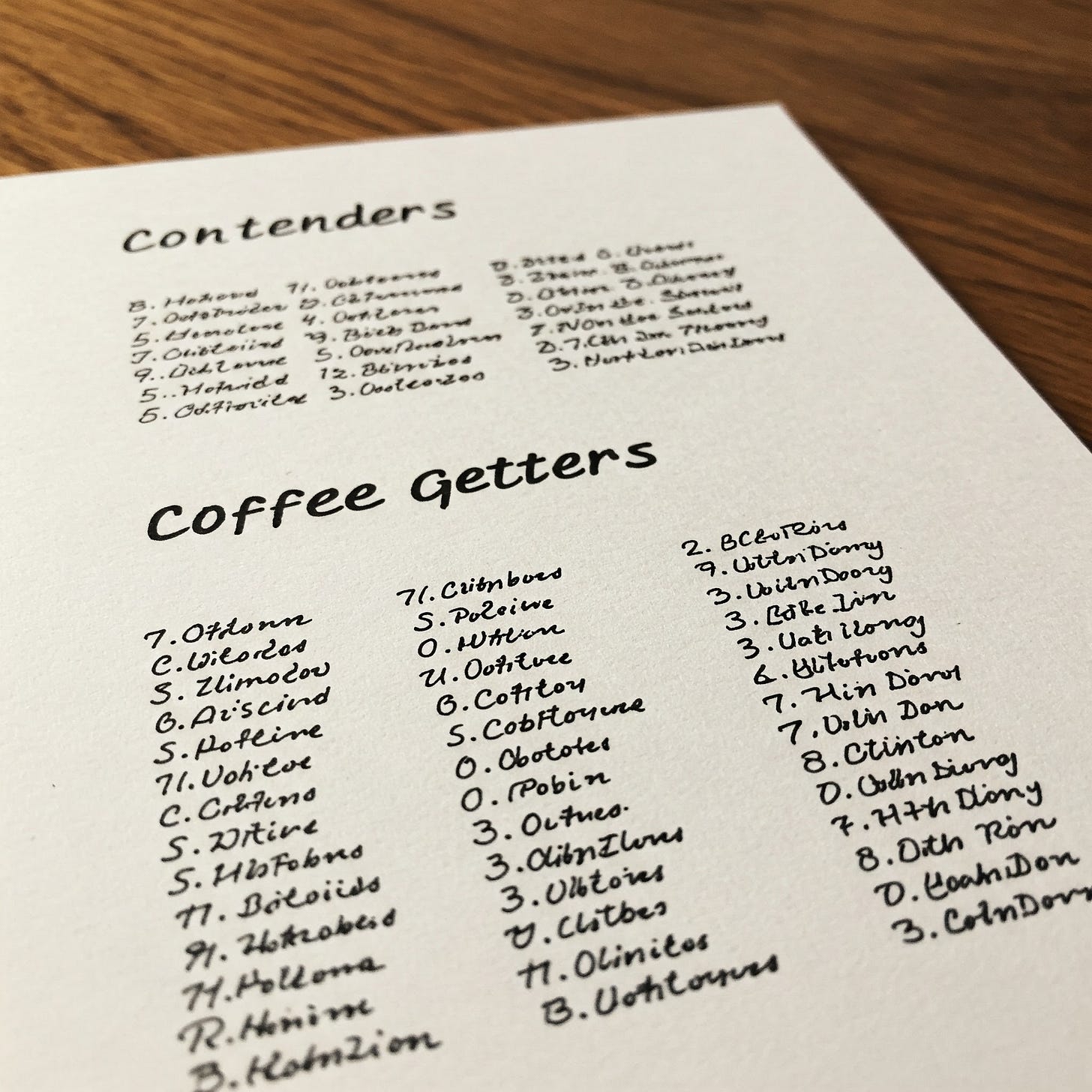

As a result, students leave PME with ample practice writing poorly but convinced they are competent writers. Many only become aware of their writing weaknesses when they submit their first product to a commander or chief of staff, written to the PME standard they’ve learned: substantively solid but poorly structured, unclear, wordy, and full of errors. If they’re lucky, they get an ass-chewing, some mentorship, and a second chance. If they’re not, their boss simply says, “noted” and moves their name from the “contenders” list to “coffee getters.”

This brings us back to authentic assessments. How can PME measure students’ writing skills with assessments that “approximate conditions under which the graduate would be expected to [write] in the operational environment”?

If we’re honest, a truly authentic writing assessment would be completely unfair. The grader would do what commanders and chiefs of staff in the field often do—judge an officer’s competence and professionalism based on a cursory scan of their first written product.

Clearly, these types of arbitrary judgments have no place in PME. Just because field commanders evaluate officers using flawed heuristics doesn’t mean PME instructors should follow suit. Nonetheless, there are lessons to be learned for both PME students and institutions.

For students, don’t be lulled by successful PME writing; chances are high it didn’t prepare you for writing in the field. After you graduate, harsh judgment awaits. Your first written product in your next job will affect your professional reputation, for better or worse. If you want it to be for the better, your writing must not only be substantively sound but also well-organized, easy to read, free of errors, and presented neatly and professionally. These things matter—don’t let weighted PME rubrics mislead you.

For institutions, a first step toward improving PME writing is acknowledging that we cannot teach students to write well on the cheap. Developing students’ writing skills requires time and attention. PME must treat writing as a core competency, not an afterthought. Instead of relying on the “twofer” strategy, PME should provide dedicated courses with a primary focus on developing writing skills.

Furthermore, PME should prioritize quality over quantity. More writing doesn’t lead to better writing—better writing does. Schools should assign fewer papers while setting higher standards, requiring multiple drafts with feedback from both instructors and peers at each stage. Throughout the process, instructors must hold students accountable for subpar writing. Even when rubrics emphasize content, instructors cannot let poor organization, unclear prose, or excessive errors pass without comment.

Professionals don’t learn to write well by osmosis. If we want PME graduates to write effectively in professional settings, we must treat writing as a core skill, set higher standards, and hold students accountable. Equally important, PME must stop reinforcing poor writing habits that leave graduates ill-prepared to write in the real world.

Great essay! I am, at best, a mediocre writer. Like many others, my writing is plagued by wordiness and misplaced commas—I have no idea how to explain where commas should go 😂.

That said, though many officers are bad at writing, I have little sympathy for them. They should have learned writing in college, and if they know they can’t write well then it is incumbent upon them to improve themselves. In my view, officers should not be reliant on PME to learn writing. If my writing sucks, it isn’t CGSC’s fault.

The people who need the most help, and who are generally willing to improve, are NCOs—especially more junior ones.

When I come across an NCO whose writing is horrendous, I give them four simple rules (mostly for writing emails):

1. You may not use commas.

2. Your sentences may not be longer than one line.

3. Hit the enter button twice after you type a sentence. Then begin your next sentence.

4. Read the email out loud to yourself before you hit “send.”

I know these sound dumb and simplistic. But I have seen emails transform from garbled messes to clear and concise messages almost instantaneously. Once you break an NCO of the mentality that they have to “sound military,” they turn on their brains. With these contraints they naturally start writing much more clearly and they structure their thoughts much more logically.

There’s definitely more you can do to teach them, but these constraints stop the bleeding.

Thoughts?